Here we go again…—that moment when you finally realize that all your efforts toward achieving perfection will never be enough.

Seizing the Wabi-sabi

Probably wabi-sabi was first named for what happens to pottery subjected to the hellish temperatures in kilns, around 2,000ºF (~1100ºC). During the firing, the intense heat vibrates all the bonds that hold the minerals together until they come apart, and their constituent ions and molecules cruise around in a melted bubbly mixture that resembles lava, an igneous rock.

Probably wabi-sabi was first named for what happens to pottery subjected to the hellish temperatures in kilns, around 2,000ºF (~1100ºC). During the firing, the intense heat vibrates all the bonds that hold the minerals together until they come apart, and their constituent ions and molecules cruise around in a melted bubbly mixture that resembles lava, an igneous rock.

The kiln cools, and the pottery solidifies. Sometimes a gas bubble in the glaze pops at that moment and a little crater forms. Or maybe the glaze didn’t come out with a uniform color, or part of it dis-adhered from the pot and crawled away. Or the tea bowl sagged into another pot.

Classic wabi sabi, telling the story of a unique and unrepeatable moment of creation, fired and frozen in time.

Such wabi-sabi moments manifest keshiki–the landscape of the clay; these imperfections do not in any way interfere with the functionality of the piece, and it would be enormously wasteful to throw something useful away because of a surface imperfection.

One over Infinity

I like to think of firing pottery as a sort of ‘backyard metamorphism’ that changes the pottery, essentially a sedimentary rock, into a metamorphic rock.

I like to think of firing pottery as a sort of ‘backyard metamorphism’ that changes the pottery, essentially a sedimentary rock, into a metamorphic rock.

I have even made the statement publicly, that kilns are science laboratories in which ceramic artists perform experiments in geology and thermodynamics, which is a branch of science that deals with the advanced secrets of the Universe.

We have learned a great deal about the behavior of matter through experiments that rudely resemble the actual physical universe, tweaked by precise mathematical equations that ignore much of the almost infinite variation therein. Somehow we get close enough that the pieces fit together in rude sorts of ways.

Potter’s kilns on the other hand, much more closely approach the actual imperfection that brought us all the rocks on Earth. And the universe. With a great deal of faith, you consign your piece to the kiln. The wabi-sabi is impossible to know or quantify. There are no round frictionless cows.

Pray to the gods of fire, electricity, gravity and magnetism, that what comes out resembles the vision in your mind. Let me take a moment to calculate the likelihood of that.

One over infinity.

There’s always some wabi-sabi.

A Wabi Sabi Moment with Georgia O’Keeffe

I grew up looking at O’Keeffe art—being that she lived in New Mexico, where I was born and spent most of my life. I’d seen her paintings in books and posters for years. Standing in front of famous paintings in real life—no photograph holds a candle to that experience. It’s not just the colors being more alive, or that you get the true idea of the size of the painting. You are close, very close to the act of creation.

I grew up looking at O’Keeffe art—being that she lived in New Mexico, where I was born and spent most of my life. I’d seen her paintings in books and posters for years. Standing in front of famous paintings in real life—no photograph holds a candle to that experience. It’s not just the colors being more alive, or that you get the true idea of the size of the painting. You are close, very close to the act of creation.

And once, I stood mesmerized in that very moment, as close to a painting as the cops at the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum in Santa Fe would allow. I could not take my eyes off it: a single paintbrush hair embedded in a stroke of color. I felt as if I was there in that one moment when Georgia O’Keeffe stood before this very canvass. A million brush strokes in her long life of painting…and there’s this one that put in that single, unique moment of exquisite wabi-sabi.

It was breathtaking.

I’m glad she didn’t see the hair; surely she would have plucked it out. I would have, in the name of flawless perfection that is found only as a concept within the part of the human brain that dreams of round frictionless cows.

Imperfection: it’s what makes the world

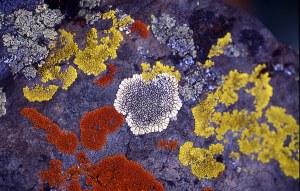

Not even crystals are perfect; they all have wabi-sabi.

They found this one really big chunk of blue diamond, cut all the wabi-sabi away, until it was perfectly huge. Hugely perfect. They called it the Hope Diamond—hoping for another humongous one like it.

One over infinity. It happens. But it’s all the other instances of imperfection that comprise the whole dang universe. The perfect parts are so few as to barely exist at all.

I’ve never made a perfect pot, never wrote a perfect book, never been a perfect anything. I’ll continue to put it out there, though, as long as I have a heartbeat. I am but a fragment of the whole wabi-sabi universe unfolding.

I just don’t know what else to do with myself.

You must be logged in to post a comment.